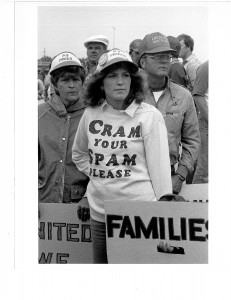

When Austin, Minnesota workers at Geo. A. Hormel & Co. went out on what would come to be seen as THE strike of the decade 25 years ago come this August 16, signs that read “Jay Hormel Cared” began appearing on the front lawns of strikers and supportive townsfolk. The suggestion: Company attitudes toward the area and the workforce had changed for the worse since the benevolent days of a previous generation of company executives, including Jay Hormel. Was the crisis really as simple as that?

Well, in a way, yes.

In the 1980s, I lived and worked in Austin as part of a labor consulting firm that supported the strikers. I had previously been to many company towns—a category that surely included Austin—from Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina to Gary, Indiana. But I had never reflected that much on the phenomenon. Twenty-five years later, I have researched and published a historical survey of America’s company towns. That work casts interesting perspective on the choices made by businesses past and present.

Over the decades since the early 19th century, there have been a lot of American company towns—perhaps as many as 2,500. (When she learned that I was writing a book on these communities, a historian at one New England industrial museum remarked: “Oh, how many volumes will it be?”) And as you might expect, U.S. company towns vary greatly. But at the extremes, there are two distinct models: The benevolent, paternalistic town, typified by chocolate man Milton Hershey’s Hershey, Pennsylvania and today’s Corning, New York, hometown of high-tech glassmaker Corning Inc.; and the “Satanic mills” model, where workers are treated almost like prisoners and exploited in every way imaginable, from being paid low wages for brutal labor to being required to shop at the company store. The clearest examples of the latter model were in coal country, from such burgs as Harlan and Jenkins, Kentucky to Trinidad, Colorado.

As recently as the 1970s, Austin clearly followed the benevolent, paternalist model. It took a militant 1933 strike and years of labor militancy, but by the 1940s the company and its workforce had settled on a social compact that included profit-sharing, incentive pay, a pace of work determined not by company foremen but by the workers themselves, and Hormel Foundation support for area charities. “If a man is going to work for anybody else, it’s hard to beat Hormel,” one worker told an industrial-relations researcher in the 1950s. Seventy-five percent of Austin residents owned their own homes in that decade, and virtually all workers possessed recent-model cars.

But many Hormel managers were never altogether content with the arrangement and by the 1980s, the increasing power of low-wage, antiunion companies in meatpacking seemed to persuade Hormel management that the social compact should be radically altered. Even though their company was highly profitable, if they didn’t cut Austin workers’ pay dramatically, Hormel executives argued, these low-wage outfits would run them out of business. So they opted to move closer to the “Satanic mills” model that I have described above. They weren’t alone: Across the Midwest, once-prosperous meatpacking towns are now the scenes of trailer-park blight, crime, and poverty.

However, one thing becomes clear as a result of an in-depth look at industrial-relations practices across America’s company-town past. Pure economics are never the sole determining consideration in managerial decisions about human relations. It helps to be rolling in money, of course. But such factors as the national political climate, the availability or scarcity of a needed labor force, and concern for positive public relations and consumer brands are all taken into account in corner-office policy-making. And then there’s just good business sense: Fair dealing, good behavior, and mutual trust are key to making markets possible; why shouldn’t they likewise be key components of human-relations policies?

![2468089071_d92f2e1123_z[1]](http://hardygreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/2468089071_d92f2e1123_z1-225x300.jpg)

In 2009, Hormel enjoyed net sales of $6.5 billion, and earnings per share were up 22%, according to the company’s annual report. Yet the events of 25 years back remain etched in many Americans’ memory. In an attempt to turn the page, Hormel tries to pretend that nothing ever happened—as if it did not unilaterally reduce its workers’ wages and require the deployment of the Minnesota National Guard and a legion of other police to break a strike that had become a national cause celeb among labor supporters. A two-tier wage structure put in place following the strike is still in force. But if Hormel really wants reconciliation with the past, a good place to begin would be with a reconsideration of the enlightened policies it forsook in 1985.

For another look at the Hormel events check out Minnesota Public Radio’s report: http://minnesota.publicradio.org/display/web/2010/08/09/austin-at-a-crossroads-part1/

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an email. I’ve got some creative ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it develop over time. Also, please check out my site http://www.facebook.com/notes/bath-supplies-deals-online/review-of-solid-brass-toilet-roll-paper-holder-chrome/139205739523714