Sunday, October 31

I have not seen Wes Anderson’s new movie, The French Dispatch (available only in theaters), but I look forward to doing so. Centered on a fictional but nonetheless familiar magazine based in Paris and greatly resembling The New Yorker, the film has drawn glowing notices in the Times and—surprise, surprise—The New Yorker. The flick consists of four narratives—one featuring a reporter, another considering an imprisoned painter, another looking at life via the eyes of a James Baldwin-like writer, and finally, one focusing on a 1968 Paris Spring student firebrand.

Anderson is perhaps the most literature-influenced film director since Jean-Luc Godard. His previous movie The Grand Budapest Hotel drew inspiration from the work of once-popular and now largely forgotten novelist Stefan Zweig. This time around, Anderson has reportedly instructed his actors—including such regulars as Owen Wilson and Bill Murray along with the suddenly ubiquitous Lea Seydoux—to check out the writings of Mavis Gallant, a Paris-based New Yorker writer of yore.

But why? Gallant certainly knew her way around a stylus; her Paris-scribbled short stories are impressive even if they focus on such uninspiring protagonists as a former German POW, a nose-to-the-grindstone Riviera hotelkeeper, and a hard-pressed art dealer. She also penned very lengthy dispatches about the 1968 events that ran as a two-part feature in The New Yorker. These are likely what Anderson had in mind when advising his cast. And there’s where the problem lies: The jottings capture the flavor of events but give us little more.

So what did Gallant make of 1968’s happenings? It’s not altogether clear. Gallant’s “The Events in May: A Paris Notebook” adopts the form of a diary, with entries focusing on the garbage in the streets, food shopping and shortages, disruptions of daily life, the looks of the protesters and of the Gaullist counter-demonstrators, radio news reports, her own dreams, and brief conversations held with a range of friends and frenemies.

She is stingy with her compliments. “Why do they keep on about Marcuse? Except for Z.’s dentist friend, no one even knows who he is,” she kvetches. “How can you talk about the Spanish Civil War to people who don’t even know what happened in 1958, or 1961, or what the O.A S. was about?” she whines.

But if she finds the student protesters unwashed and uninformed, the pro-de Gaulle counter-protesters are even less admirable. A vast May 30, Champs-Élysées-filling right-wing crowd has only summoned the courage to turn out, she believes, because the French army now has tanks and troops surrounding Paris.

“I am acutely unhappy at the slogans I am hearing: ‘La France aux français,’ ‘La police avec nous.’ I find this ugly. When I heard the students last week shouting ‘Nous sommes tous des juifs allemands!’ I thought they were speaking to their parents. Today the parents answer: ‘La France aux français.’”

At their rallies, the young folks were idealistic; these revanchists are repellent. “I liked those kids. They were generous, and they were very brave. And when they shouted a slogan they were always asking for some sort of justice, usually for someone else. What is generous about ‘La police avec nous’?” Afterwards, Gallant only regains her equilibrium via “an enormous dinner with floods of wine.”

In the end, the writer offers no real stock-taking of the May events and their consequences. There is, she says, “No explosion de joie, as papers suddenly have it—just depressed feeling, as after an illness.” News reports convey the notion that the whole thing had been nothing but a game. As if by magic, the gasoline stations suddenly have plenty of petrol, the shops have lots of food and once-scarce sugar, and an “enormous tricolor is hung from the top of the Arc de Triomphe—[the] flag usually kept for July 14th and important state occasions.”

People ask themselves: What has been gained exactly? The “tone of conversations is relief, bewilderment, disappointment, fatigue. It is like the feeling after a miscarriage—instant thanksgiving that the pain has ceased, plus the feeling of zero because it was all for nothing.”

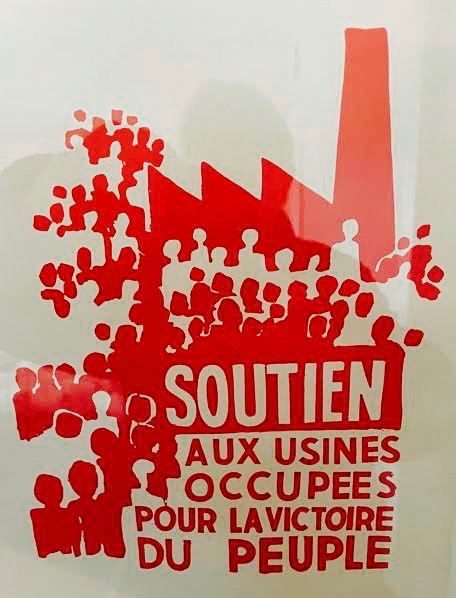

And that’s about all Gallant has to offer in the way of evaluation. And yet May of 1968–with its factory occupations, three-week General Strike involving 10 million people, and near overthrow of Charles de Gaulle—lives on as a stirring inspiration to progressives: “be reasonable—demand the impossible,” as one Paris graffito had it. Perhaps Mavis was simply too exhausted to deliver much more than she did.

Dinner: Pasta e ceci and a green salad.

Entertainment: Britbox’ policier The Long Call.