Wednesday, June 3

Tomorrow, it’ll be 13 weeks since we left New York City for our East Hampton pandemic retreat.

Without jobs or even solid gigs, it may have been mostly habit that held us to the city. There were times when we put a bit of effort into cultural pursuits—hearing jazz or classical performances, visits to museums, jaunts to particular shops where we often just looked at stuff without buying. Other times, we just hung out, enjoying the vibe. Now, Gotham may never again be what it was. To return there may be like subjecting oneself to the memory of a lost world.

New York was never to me the near-paradise conjured by Stefan Zweig in his memoir of pre-World War I Vienna, The World of Yesterday. But the feeling of a lost world may be somewhat similar. Zweig—a highly popular writer in his time if not so well remembered today—describes that Hapsburg Empire capital as a center of music and learning, a place where he became acquainted with cultural luminaries ranging from Rainer Maria Rilke to his friend and fellow writer Romain Rolland. Then came World War I and, all too soon, the Nazis.

Zweig, who had thought of himself less as an Austrian than as a citizen of Europe, fled to London, New York, and ultimately to South America, where despair led to suicide. He wrote that “the past was done for, work achieved was in ruins, Europe, our home, to which we had dedicated ourselves had suffered a destruction that would extend far beyond our life. Something new, a new world began, but how many hells, how many purgatories had to be crossed before it could be reached!”

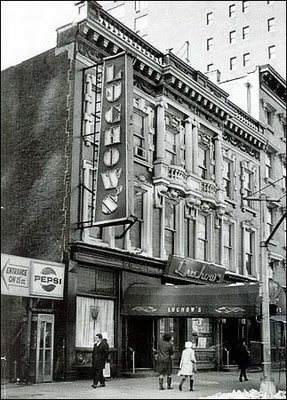

In a vandalized New York, broken glass can be swept up and windows replaced. Even burned buildings can be reconstructed. What worries me more are the small institutions that could very well become casualties of the current catastrophe. And these—not Dunkin’ Donuts but the intimate Jack’s Coffee or even the very hip Think Coffee—are what make New York what it is. I was glad to hear that Small’s, the tiny West Village jazz club, was sponsoring some streaming concerts in the next days. That seemed a sign that the club, and its nearby sibling Mezzrow, sees itself as having a future life.

Food halls like Essex Market on the Lower East Side are likely to suffer. That mid-size emporium is made up of many independent vendors including sellers of Italian and Latin grub, cheese, seafood, and baked goods.

Dozens of small art galleries could well disappear. And if the citizenry is poorer and global tourism put on hold, even much larger cultural institutions could be threatened. Does the avant-garde New Museum have an endowment large enough to weather the current storm?

Optimists will say that, no matter how it changes, New York will always be New York. People and places disappear, but the essence remains.

Another memoir of a vanished world is Dan Wakefield’s New York in the Fifties. That author ends on a wistful note, cognizant of the many unwelcome changes that have come since he departed the city in the early 1960s. Yet he concludes with a sentimental poem about New York by the radical John Reed: “Who that has known thee but shall burn//In exile till he come again….”

On a less elevated note, Peapod made its food delivery today at around 6 p.m. Of the 43 items we ordered they delivered 29–and no receipt to tell us how much we were charged. Still no toilet paper, of course, and no mushrooms, sugar snap peas, walnuts, or garlic. Does our $20 tip seem warranted?

Dinner: Spaghetti with fried eggs, green salad.

Entertainment: More episodes of the Belgian policier The Break.