Tuesday, August 11

I’ve been reading some extremely literate mysteries by the English writer Julian Symons. So far, I have read The Belting Inheritance, The Detling Secret, The Immaterial Murder Case, The Color of Murder, The End of Solomon Grundy, and now The Blackheath Poisonings. The Detling Secret and The Blackheath Poisonings are set among the wealthy in late 19th century England—and so, in the country-house-mystery territory beloved by fans of Agatha Christie and scorned by such American masters as Raymond Chandler. But Symons is much more than a “cozy” mystery writer: His characters are complex, his prose is finely wrought, and his plots only give away their secrets on the final pages.

The Blackheath Poisonings contains a typically memorable exchange between two doctors. Considering the death of the head of the Vandervent family, the elder Dr. Porterfield counsels against an inquest and a post-mortem. The cause of death was just ordinary gastric distress, he says, and any suggestion to the contrary would merely cause embarrassment to the influential family. His younger colleague, Dr. Hassall, notes that established medical ethics insist that no death certificate should be signed if there is any uncertainty about cause of death. “A post-mortem is scandalous in itself,” says the older man. “If it should prove that the death was natural, then the doctor who had been so disobliging…could expect to lose a large part of his practice. Half at least…and it would be the better half that went—the carriage trade, as vulgar people call it.” In the end such cynicism wins out, and there is no post-mortem—which would have discovered poison in the dead man’s system.

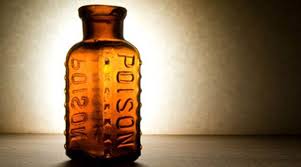

Poison is out of favor today. When was the last time you read about anyone being poisoned, other than as a result of corporate malfeasance? No, knives or other sharp instruments are still allowed, but, other than COVID-19, the favored instruments of death today are firearms or explosives. I mean, guns are just so accessible, and you practically need a prescription to get any poison other than weed killer.

And speaking of digestive worry, Emily recently informed me that she wanted to take onions off of our shopping list. It seems the ever-informative Times is spreading the news about a salmonella outbreak in the current onion crop. Why some 500 people in the U.S. have been infected!

Seems like we have better things to worry about. Any onions we use are likely to be well cooked, and we always wash our knives and cutting board with Dawn dish soap and water. Meanwhile, if salmonella is your concern, 1,000 cases this year have been linked to the eating of poultry.

Back to Victorian times. “One of the main reasons why poisoning became such a common means of murder in the Victorian era was, quite simply, ease of access,” notes a British Library blog. “Cyanide was everywhere, in everything from paints to daguerreotypes to wallpapers.” But the poison of choice was arsenic, which was both tasteless and odorless. “Readily available in a staggering array of forms from flypaper to cosmetics, it was comparatively difficult to detect,” says the blog.

So there you have it: more crimes of opportunity.

Dinner: grilled pork chops, corn on the cob, and a lettuce and tomato salad.

Entertainment: Netflix’ Cuban spy drama Wasp Network.