Monday, December 7

The global pandemic seems to have triggered an openness to workplace change among employers.

The New Zealand company that imports and distributes Lipton Tea and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream has just announced that it is moving to a four-day work week, with no change in pay, for its regular employees.

Meanwhile, of course, a large number of companies are allowing, even encouraging, employees to work from home (thereby saving money on office rent). And in a move that not everyone regards as positive, Uber and its allies recently won a California state referendum that encourages the spread of “gig employment,” under which workers have the freedom to come and go as free-lancers—but also employers have few responsibilities toward said workers.

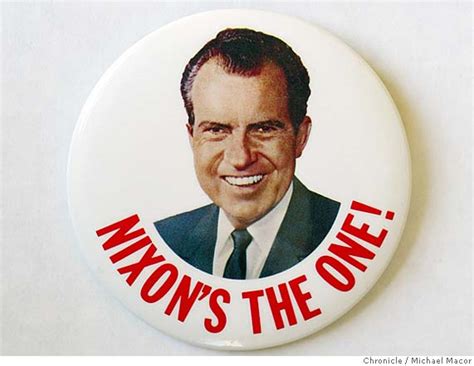

Unilever New Zealand’s move toward a four-day workweek has prompted many to ask: Why didn’t this happen sooner? After all, Vice-President Richard Nixon predicted a move to such a shorter workweek back in 1956.

Inertia and bosses’ natural resistance to any kind of pro-worker reform are always at work, of course. Even though Henry Ford’s auto-plant workers had enjoyed an eight-hour day and 40-hour workweek since 1926, it took years for the U.S. to adopt such standards more broadly—the twelve-hour day was standard in much of heavy industry into the 1930s. The Fair Labor Standards Act, signed into law in 1938, set a ceiling on hours at 44 per week, then 40 per week two years later.

And different industries have different limitations. In the steel industry, which in America entered into its prime around the turn of the 20th century, plants ran flat-out, 24 hours a day. Twelve-hour work days meant hiring only two shifts per day; a switch to eight-hour days would mean three shifts, increasing labor costs by 50%. In contrast, lots of “knowledge work” can be and is done anytime, anywhere. The idea for rum raisin ice cream could have arisen while some employee was having his evening dessert pudding.

Moreover, Unilever has a lengthy history with what has been termed welfare capitalism. The New Zealand unit is a descendant of the British company, Lever Brothers, which was one of several companies to create model company towns in the 19th century. Port Sunlight, as the Lever town in Merseyside was called, housed a company soap works and a model village for workers, featuring pretty cottages, an art gallery, a hospital, schools, a concert hall, a swimming pool, and churches. William Lever, who became the Viscount Leverhulme, said his goal was to “socialize and Christianise business relations.” The better environment, he thought, would mean happier and more productive workers. Port Sunlight was an inspiration for other model company towns, including Hershey, Pennsylvania and Pullman, Illinois.

Also among those calling for a four-day workweek is former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang. Companies that adopt such hours will, he says, draw the best talent, just as Henry Ford did in the 1920s.

Dinner: Avgolemono soup and a lettuce and avocado salad.

Entertainment: the final episode from season two of the Swedish version of Wallander on Kanopy, plus an episode of The Queen’s Gambit on Netflix.