Monday, May 11

The most visible minority presence in the Hamptons nowadays is Latino. But of course, it wasn’t always that way.

Latin American immigrants have been coming to the Hamptons for decades, drawn here by the promise of construction and other work. Decades back, Colombians, Costa Ricans, and Mexicans were the first Latinos to arrive, followed by Ecuadorians, Guatemalans, Hondurans, Salvadorans, Venezuelans, and others.

I’m quite aware of the Ecuadorian presence, as a result of conversations with construction workers and waiters, and thanks to the presence on East Hampton’s North Main Street of a bodega called Mitad del Mundo—named after a place in Ecuador that’s near to the equator.

Some 15% to 20% of East Hampton’s current population is Latin, along with over 25% of the school population. Between 1980 and 2000, according to the U.S. Census, the Latino population grew tenfold, to 2900. Such figures, of course, are likely a huge underestimate.

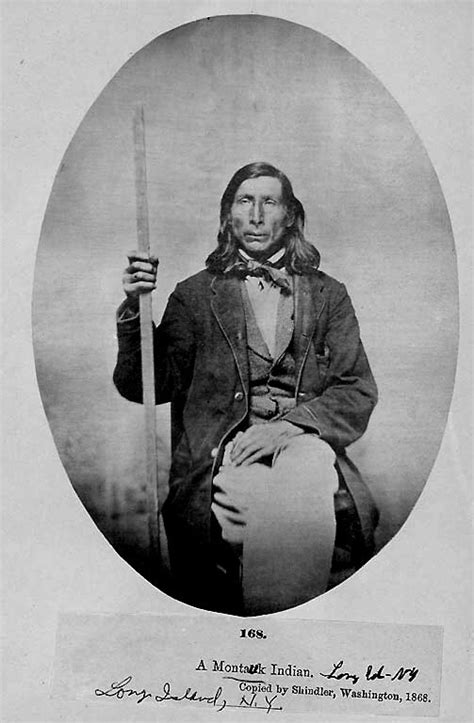

In earlier decades, the larger minority groups were Native American and African American.

As I described in an earlier post, it was the Montaukett Indians who sold the East Hampton land to whites in the 17th century. For many years thereafter, that Native American group kept to itself, concentrated in the Montauk area. The white settlers in East Hampton stuck to farming and occasionally harvesting a “drift whale,” a leviathan who’d somehow beached itself. By law, householders were required to turn out and help with the smelly, disgusting labor of hacking up a dead whale, whose blubber could be turned into valuable lamp oil.

This whale fat gradually became an important source of income for the farmers. And by 1670, they realized that they didn’t just have to depend upon fate to send a whale their way—they could go out to sea and kill the right whales that ventured near to the East Hampton coastline.

The East Hamptonites began forming private whale companies, outfitted with sturdy boats, harpoons, oars, a drogue (or sea anchor that got affixed to a wounded whale), and huge kettles for cooking down blubber. Each boat required a crew of six strong men.

Re-enter the Montaukett Indians. In a move that would be the envy of many gig-economy workers today, the Indians began negotiating labor contracts with the East Hampton whites. These contracts generally committed individual Montauketts (who made their marks on the dotted line) to a season of whale hunting, in exchange for which the Natives would get half of the harvested whale meat.

Why did the Montauketts do it? There’s evidence that they were gradually drawn into a kind of debt peonage, promising to labor until they’d paid off what they owed. Like the whites, the Indians had come to appreciate the finer things in the way of European-made goods that could be obtained for hard cash.

This sort of whaling seems to have come to an end after about sixty years, circa 1730. There had been massive overfishing of the shallow-water whale population, and after the mid-1700s, all that remained was deep-water whaling, as was conducted out of Sag Harbor and Nantucket. Along with the waning of East Hampton whaling came that of the Montauk tribe. By the 1770s, there were only thirty Indian families remaining, the others having wasted away due to poverty and white-men’s disease. (Most of the above information is drawn from T. H. Breen’s Imagining the Past: East Hampton Histories.)

One exception: Stephen Taukus “Talkhouse” Pharaoh, a late 19th century survivor. Talkhouse, a prodigious walker, claimed a variety of exploits, including prospecting for gold in the California gold rush, serving in the Union army, winning a walking race from Boston to Chicago, and participating in P. T. Barnum’s circus. His name lives on thanks to local monuments and to the Amagansett rock ’n’ roll club named for him.

Tonight’s dinner: grilled pork chops, baked potatoes, and brussel sprouts.

Entertainment: back to Occupied, the Norwegian futuristic thriller that contemplates a Russian power grab of Norway’s North Sea oil.