Sunday, May 17

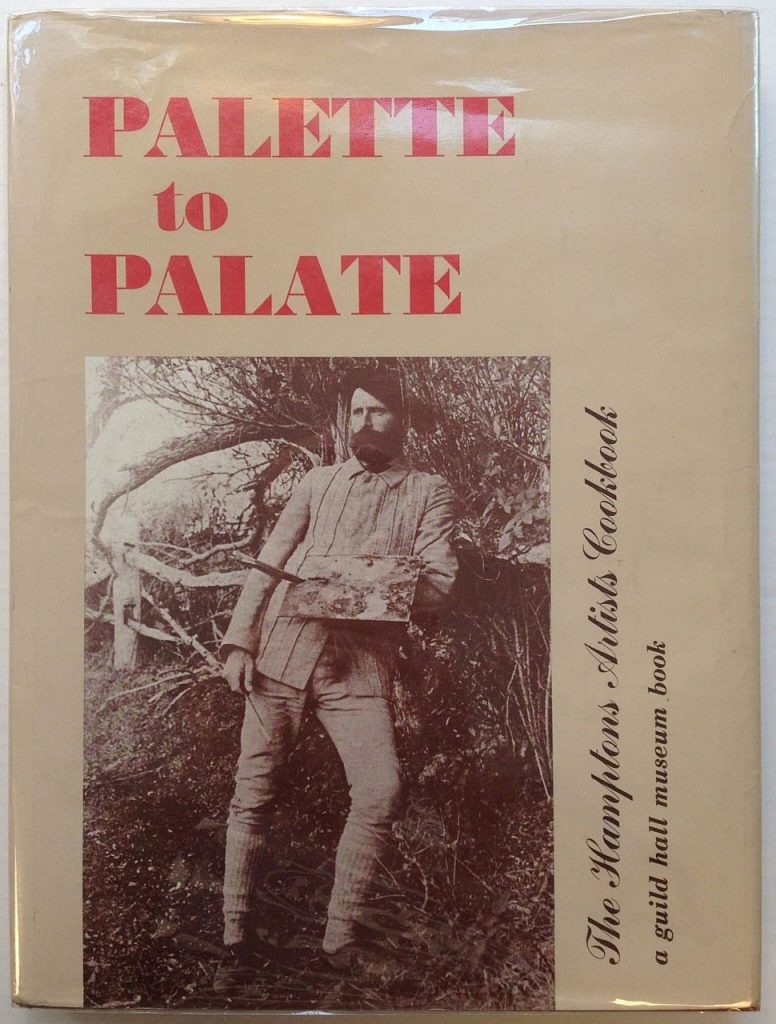

Having read my blog entry about the Home, Sweet Home Cook Book, a friend has emailed me information about a Hamptons artists’ cookbook, Palette to Palate. It was published by Guild Hall Museum in 1978, contained recipes from 130 local artists, and featured illustrations and autographs from Andy Warhol, the de Koonings, and Lee Krasner. The recipes tend to be a little more sophisticated than those in Home, Sweet Home: Krasner’s contribution, for example, was a “hominy puff with cheese, herbs, or crabmeat.” Art-book dealer Argosy lists a first edition of the book as available for $4,000.

Back to grimmer stuff.

Emily has e-mailed me a Twitter timeline of New York City pandemic developments starting in March. It seems that for once in our lives at least, we’ve been ahead of events.

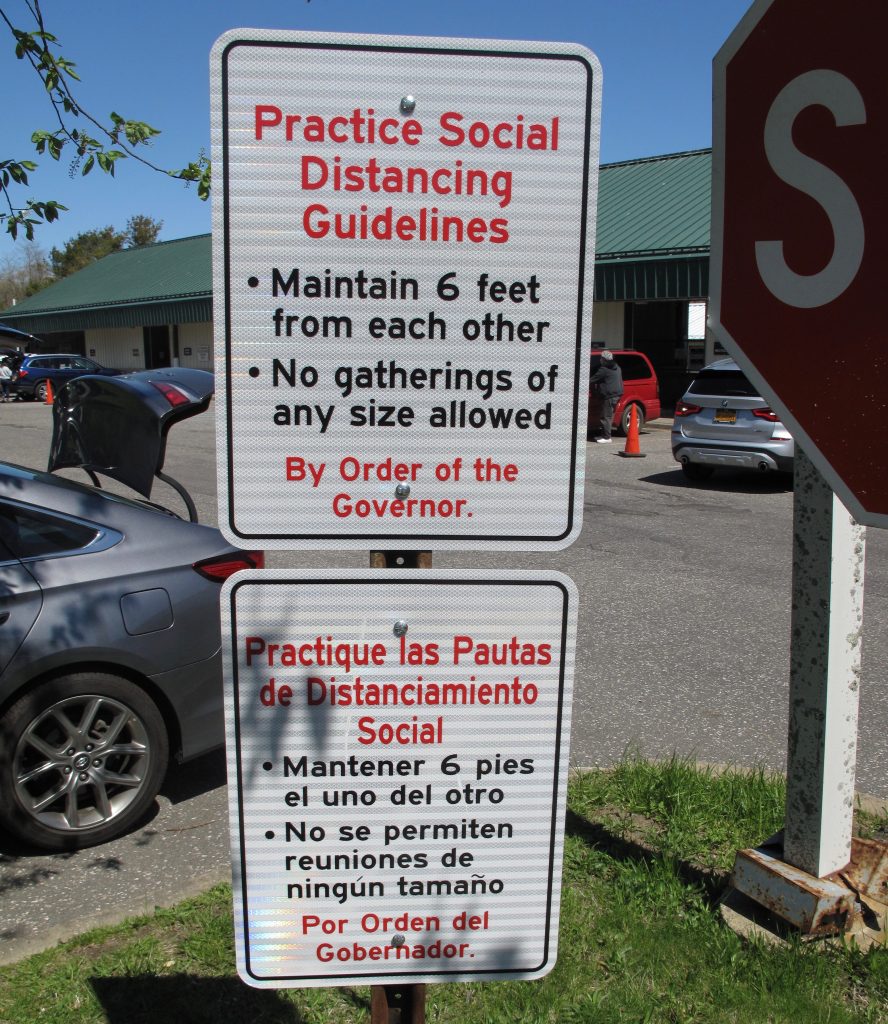

We came out to East Hampton on March 5—the first New York City case of COVID-19 had been reported on March 1. On March 7, two days after we came out, the governor declared a state of emergency in New York State, and five days later he banned any gatherings of more than 500 people.

That same day, March 12, Mayor de Blasio declared a state of emergency in New York City, and the next day, it was announced that New York State had the most cases of the disease in the U.S., as new cases jumped 30% overnight. (And these, as I always have to remind myself, were just the reported cases. Many people had it but were asymptomatic.)

On March 20, Cuomo ordered nonessential businesses to keep 100% of their workforces at home. By the end of the month, New York State had become the coronavirus epicenter of the world, as its number of COVID-19 cases exceeded those in China’s Hubei province where the outbreak began.

Only on April 15 did Cuomo order everyone to wear face masks. Today, epidemiologists make a convincing case that THIS and social distancing are the most important things of all.

One problem of course was the shortage of masks. Officials were saying to leave the available masks for the professionals who really need them; don’t try to hoard masks; wear a bandana around your face, make your own mask, etc. Vendors began offering lots of homemade masks online, and Emily ordered several for us on April 16.

On May 1, Cuomo announced that public schools in the state would remain closed for the rest of the school year.

By mid-May, 1.8 million state residents had filed unemployment claims—six times the number filing claims during the 2008 financial crisis.

And that brings us to where we are.

The timeline is a bit puzzling to me: Events seem to move both quickly and slowly at the same time.

The first case appeared in China in December of last year. In the U.S., the first confirmed case came in Washington State in late January of this year. There was a surge of cases in Italy in February.

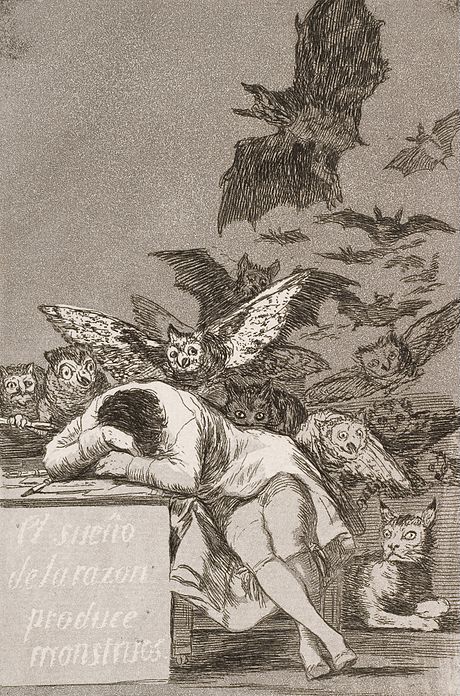

Still, no one in this country paid much attention until March, when events really intensified. Then—I know, I’m repeating myself—it took until mid-April for New York to make the wearing of masks mandatory.

There must be lessons here, and I’m sure the experts will offer us lots of them in time.

Dinner: lots of leftovers that don’t necessarily go together—mozzarella and tomato salad with balsamic dresssing, corn muffins, roasted brussel sprouts, baked potatoes with sour cream, and guacamole.

Entertainment: episodes of the Netflix nature documentary Our Planet narrated by David Attenborough and more episodes of Occupied.