Monday, September 28

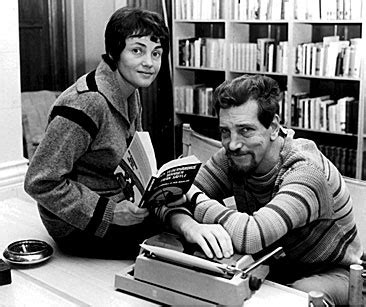

Before he co-wrote the legendary Martin Beck series of Swedish crime novels, Per Wahloo penned some futuristic dystopian books, including one that offers clues to how Trump might have played the pandemic differently, and to his advantage.

In Wahloo’s 1968 book The Steel Spring, a chief inspector of police travels away from his unnamed homeland in order to have a necessary kidney transplant. Three months later, after recovering from the operation, he attempts to go back and he’s told he cannot: all airports in his homeland are closed and all communications between it and the outside world have been cut off. A national election has been postponed due to “serious disturbances” including riots that provoked police and army intervention. Now, on top of all that, it seems likely that there’s some kind of epidemic raging, and everything has been shut down.

Doesn’t some of this sound like what we’re experiencing—or what we fear we might experience in the weeks to come?

Ministers of a government-in-exile give the policeman an assignment: sneak into their home country and find out just what the hell is going on.

This he does, and what he finds remains puzzling, at least for a while. The principal city is largely depopulated. The only authorities seem to be medical functionaries, tooling around in ambulances. He makes his way to his apartment, and later to his office, where he finds suspicious but official-seeming notices declaring that, due to the epidemic, meetings of more than three persons are not permitted. Later notices announce a “total curfew.”

When he encounters a few, self-isolating citizens, they fear him. They attempt to barricade themselves in their apartments. They seem more wary of the authorities than they do of the epidemic.

The Steel Spring is not a great book—it’s far from matching the level of excellence set by the Martin Beck series. About halfway through, the volume begins to seem padded—or maybe the plot is just overstuffed.

But the reader’s suspicion that perhaps there was no epidemic—that it was all a deception meant to cover up a political takeover—is dispelled. There really is an epidemic. AND, there has been a political takeover as well—a takeover by doctors!!

With its persistent betrayal of working-class voters in favor of big business, the social-democratic political establishment has discredited itself. About the only authority left with any credibility is the medical establishment—and boy, do they know it. Now, with their dictatorial response to the epidemic, the doctors have likewise discredited themselves.

So here, at long last, is my point: Trump should have just deferred to the medical authorities. Then, when their methods became too heavy-handed or their pursuit of a COVID-19 cure took too long, he could blame them. Hey, I let these guys—Fauci and the witch doctors—take charge, he could say. And they failed us!

As we know all too well, Trump loves blaming—and firing—other people.

But he didn’t do that. Instead, insisting that he was in command, he regularly issued wild, fantasy cures and predictions: The sickness will magically disappear. Drink bleach! Shine a light in the body. Hydroxychloroquine is a miracle cure. Very soon, there will be a vaccine.

Will Trump pay the penalty on election day? Maybe. As he often says, we’ll see what happens.

Dinner: turkey chili and a lettuce and radishes salad.

Entertainment: Episode three of Ripper Street on Britbox, followed by more episodes of Borgen on Netflix.