Saturday, December 5

Do you shy away from film documentaries? Does the current and possibly most dangerous COVID-19 surge have you wanting escapism?

Well, I know what you mean, and if there were more episodes of The Crown left for me to see, I’d undoubtedly join the queue for them.

Still there are several new documentaries that have hit my list, including two on legendary musicians, Zappa and Billie.

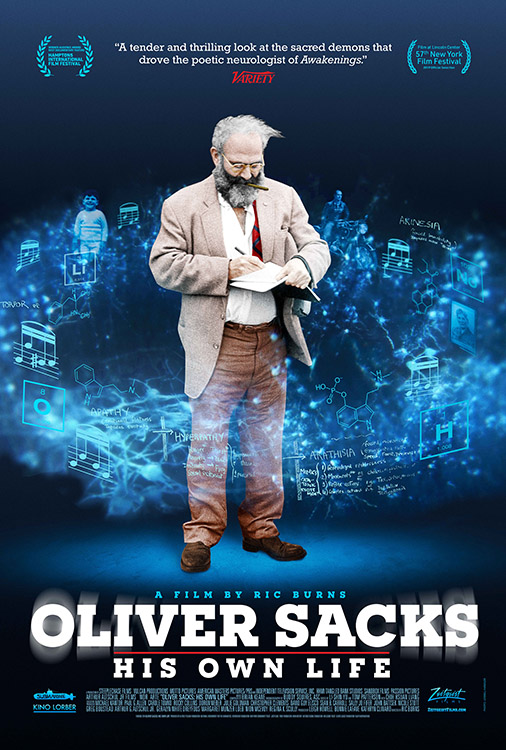

And there’s one slightly older release that’s well-worth viewing: the Ric Burns bio-doc of neurologist/writer Oliver Sacks, author of such popular books as Awakenings and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

If you’ve read some of Sacks’s work you may feel that you already know him pretty well. The Burns documentary, Oliver Sacks: His Own Life, could change your mind about that and maybe make you wonder if everyone’s life choices are little more than a series of accidents.

Sacks grew up in the Golders Green area of London, one of four sons born to a husband-wife pairing of doctors. So it seems as though his decision to become a doctor was foreordained. On top of that, one of his brothers was schizophrenic. The mystery of that malady probably inclined Oliver toward neurology.

But when his mother asked him why he had no girlfriends—and he revealed that he preferred males to females, the resulting parental explosion became another turning point in his life. Having graduated from med school at Queens College, Oxford and performed an internship in London, he moved to the United States for further internship in San Francisco and further study at UCLA.

In California, Sacks demonstrated his penchant for becoming, in the words of one of the film’s commentators, “a world-class fuck-up.” He continued his medical practice but devoted much more of his energy to weight-lifting, motorcycle riding, and to in his own words “staggering bouts of pharmacological experimentation”—mostly with amphetamines.

After moving to New York and beginning to change his ways, he turned to writing. His first book, Migrane, was not a success—and, given its departure from the conventional academic style, it drew disapproval from his colleagues. Then during one hiking vacation in Norway, he fell from a cliff and severely injured his left leg. He decided to write about that experience and his recovery in a work called A Leg to Stand On. However, that writing effort became a huge stumbling block, taking him years to complete.

Meanwhile, he continued to work as a neurologist at Beth Abraham Hospital’s chronic-care facility in the Bronx. The case notes that he kept of patients there became the source of another book—and provided the key to his engrossing and highly successful writing formula.

He began working with a group of survivors of the 1920s sleeping sickness encephalitis lethargica. These were people who were catatonic and who had been institutionalized for decades. His treatment of them with the drug L-DOPA seemed to offer relief: Some of them became able to move on their own, to communicate verbally, and enjoy music. The case notes from this experience served as the basis of a 1973 book Awakenings. And that book, in turn, provided a template for other books to come.

There’s much more on Sacks in the documentary, but for me this much was plenty. Sacks, perhaps like most of us, lived through a period of aimlessness and, to give it a positive spin, of experimentation. Then he found his gift. Some said this use of case notes to write books was exploiting his patients: Memorably, one reviewer said that Sacks was “the man who mistook his patients for a literary career.” But to me, the books are profound and humanizing demonstrations of the strangeness and surprising nature of the human mind. Rather than exhibiting his patients in “a highbrow freak show,” as another critic called it, the works invite us to consider each person’s individuality and the possibility of overcoming the most debilitating woes. Nor does the author shrink from the notion that some phenomena—autism, for instance—can be both fascinating and just flat-out mysterious.

Dinner: cornbread tamale pie and a green salad.

Entertainment: More episodes from season two of the Swedish version of Wallander on Kanopy, plus As Time Goes By season 5.