Saturday, May 16

It could be a strange summer out here. Realtors see upbeat signs: The market for summer rentals is booming, with urbanites looking for a place where they can escape the pandemic. Meanwhile, paranoia strikes deep. In the local hardware store, not far away from the bags of potting soil and cans of paint, there’s a display of stun guns. (Hey, are these essential services?)

According to one real estate broker, the “mass exodus” of folks from New York City is continuing. Those who’d arranged a rental for late summer are looking to come earlier. Meanwhile, some owners who’d arranged before the pandemic to rent their homes have decided they want to cancel such rentals and stay on. And one lawyer reports seeing a commercial-property lease tying the date for paying rent to the lifting of the New York State’s business-activity limits.

Worried that those banned from Main Beach may trespass into your swimming pool? Well, for $29.99 you can acquire a Mace brand stun gun that doubles as a flashlight. Stand your ground, refugee!

I understand that out on the left coast, certain businesses are being allowed to reopen: pet groomers, dog walkers, car washes, appliance repair shops, and any retailer who provides curbside pickup. So, the bottom line is in L.A., Fido can get a trim and a workout but a human cannot.

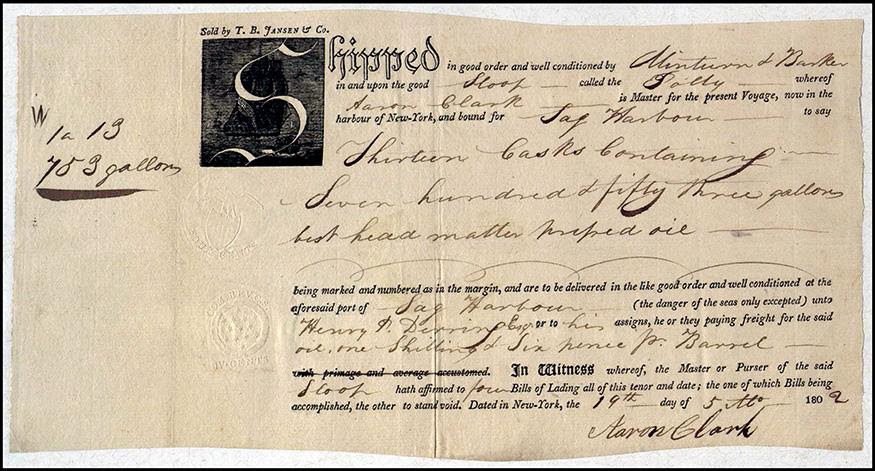

The East Hampton Library has a link to a Digital Long Island Collection of historical materials. It’s quite extensive, containing letters, diaries, photographs, deeds, drawings, and lots more.

Each week, there’s an “item of the week,” highlighted in an e-mail sent out from the library. This week’s item is a ship’s captain’s bill of lading for 13 casks containing “753 gallons of best head matter pressed” whale oil delivered to Sag Harbor but ultimately destined for use at the Montauk lighthouse.

Since much of what we do here is cook and eat, I’ve been taking a look at another of the collection’s digital holdings, a 1939 “Home Sweet Home Cookbook” produced by the Ladies’ Village Improvement Society.

Not many of the recipes hold much appeal today. One curiosity, though, is the section entitled “Suggested Menus for Large Gatherings.” Here, typical ingredients might include “one peck of tomatoes” or “20 lbs. of sweet potatoes.” There’s a chicken pie and a cranberry salad, each of which serves 50. A “molded pineapple carrot salad” that uses 3 lbs. of carrots and serves 60 to 70. And a “medium-priced luncheon or supper dish that serves 100.” That recipe uses eight lbs. of spaghetti, 4 loaves of bread, and 2 gallons of milk.

I suspect that these were recipes for a more rural, and more churchgoing society than we have today. Nor would there have been much social distancing at gatherings where these dishes were served.

Tonight’s dinner: Fresh mozzarella cheese with tomatoes and a balsamic dressing, along with cold sesame noodles.

Entertainment: Two episodes of Occupied.