Saturday, August 1

Maybe it’s a condition of rural life or something, but I seem to fall asleep early and wake up with the dawn. Rarely can I sleep as late as 7 a.m. and I am often up at 5. And that reminds me of summers in the 1960s, when my job as a copy boy at the daily Memphis Press-Scimitar sometimes required that I report by 5:30 a.m.

I was privileged to have this union-wage job—acquired strictly via nepotism—although I didn’t much like it at the time. I wanted to have the summers off as I had during my childhood. Only later would I realize that the newspaper was interesting, and that I had been exposed to a vanishing way of life at one of America’s soon-to-be-extinct afternoon papers.

Reporting at 5:30 meant going in to the paper’s downtown office at an hour when few people were around. If I turned on the radio while I downed a little breakfast, I’d hear the farm report, consisting of news about the latest commodities-exchange crop prices and advertisements for herbicides.

(An aside: During my childhood, schools in neighboring Mississippi and Arkansas had springtime cotton-chopping holidays. Rural kids had to join in the workforce to help rid the cotton fields of weeds. But before long, herbicides would do this work. That had a profound effect, even expediting the migration of rural laborers, most of them African American, to Midwestern cities.)

On the drive in to the office, I’d see few people around other than milkmen or other early-to-rise laborers. Once at the office, my work largely consisted of getting stuff ready for others who’d arrive later. That meant sorting mail or attending to a variety of machines that few remember today.

For example, there were the wire-service teletype and photo machines. In those pre-Internet days, Associated Press and United Press International teleprinters—which seemed like ghost-operated typewriters—would run all night, knocking out printed copies of stories generated around the world. There’d be foot after foot of printed-out news stories, which I had to rip off of the machines and deliver to the desks of the editors who’d consider using them in the Press-Scimitar.

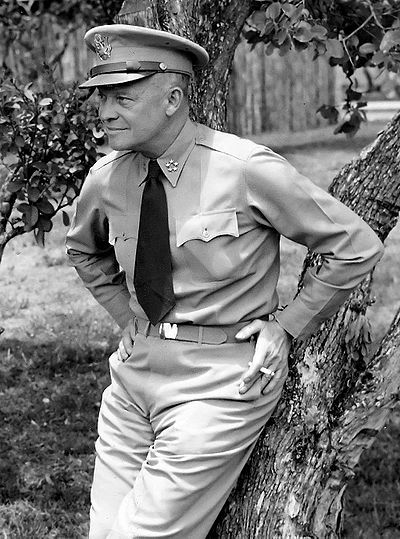

I don’t remember what outfit was behind the photo machine, but it produced reams of photos of global news coverage. Newspapers are always trying to anticipate newsworthy developments, so when the photo machine wasn’t busy delivering shots of such happening events as civil rights protests or Vietnam combat, it would fill in with other stuff. And in the summer of 1968, that meant photo after photo of former President and Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower.

What was going on? Ike had long suffered from heart problems, and news outlets imagined that he might well expire that summer. He didn’t die until the following spring, but the papers were sitting on ready just in case.

Dinner: a mozzarella-cheese and sliced tomatoes salad, with asparagus on the side.

Entertainment: Episodes of Netflix’ Tabula Rasa and Britbox’ River.