Tuesday, August 4

A spate of newspaper downsizings and closings has prompted lamentations from that bit of the press that is still standing.

The pandemic’s hit to newspaper ad sales, media giants’ takeovers, and industry consolidation have definitely led to a diminution of information about what’s going on in small-town and rural America. These may even represent a threat to democracy.

But not to get too carried away, the focus of many now-defunct newspapers was often not very profound. The Memphis Press-Scimitar, the afternoon paper that I have been writing about, was frequently viewed as a “scandal sheet” that gave exaggerated emphasis to the gaudy and sensational. Commercial pressures, a lack of resources, and the prevailing conventional wisdom stood in the way of better journalism.

Still, it was a journalism that some observers of American folkways would likely have found intriguing. It responded to the everyday concerns of the citizenry—especially when these concerns weren’t particularly weighty.

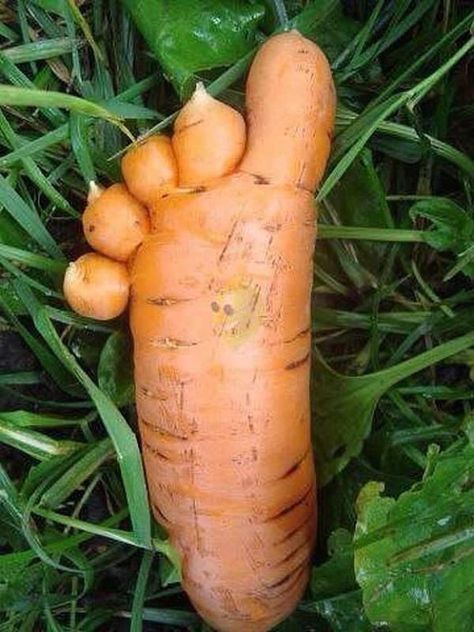

It was not unusual for a few of these citizens to show up each day at the entranceway to the Press-Scimitar’s large, open-space newsroom. And often, they’d come with stuff to show and tell—particularly, oddly shaped fruits and vegetables.

This was the oddball focus of one columnist in particular. It was a rare week that didn’t see a column by this writer accompanied by a photo of a weird veggie: a summer squash that happened to resemble Abraham Lincoln, say, or maybe a tomato that bore some resemblance to a mallard duck. The photo and profile of the vegetable would, of course, allow the writer to elaborate a bit about the life and times of the people who’d sired the veggie. What did they think of this and that?

Other inevitable fodder for stories included society fetes at the antebellum mansions of one or another grande dame; whatever-happened-to profiles of schoolboy athletes of years gone by; and reports on the current doings of famous Memphians including golf pro Carey Middlecoff and Metropolitan Opera diva Marguerite Piazza.

Memphis was just an overgrown country town, many of its citizens said proudly. Why, it was a town that had more churches than gas stations!

For a while Memphis aspired to rival big-city Atlanta. But when financial pressures prompted the Memphis government to consider shutting down its bus lines, you’d start to hear: Well, Birmingham, Alabama did that and got along just fine. So which was Memphis to be: Mid-America’s big new city—or a nowhere-ville that envied a place where Black churches got bombed by the KKK?

The Press-Scimitar closed in the 1980s—a decade that was hard on such late-in-the-day publications.

Between the growth of the suburbs, where delivery was more difficult, and the rising popularity of television news, there seemed to be little future for an afternoon newspaper in the view of The Press-Scimitar’s parent company, Scripps-Howard. The paper’s best decades had been the 1930s and ‘40s, when it sided with the uprising against Memphis’ political boss E.H. Crump and helped get Estes Kefauver elected to the U.S. Senate.

By the 1980s, though, both Crump and the newspaper’s crusading history were very distant memories.

Dinner: Pasta with asparagus pesto and a lettuce and avocado salad.

Entertainment: concluding episodes of Britbox’ policier River.