Monday, May 11

Is it possible to manufacture culture, just like automobiles and software?

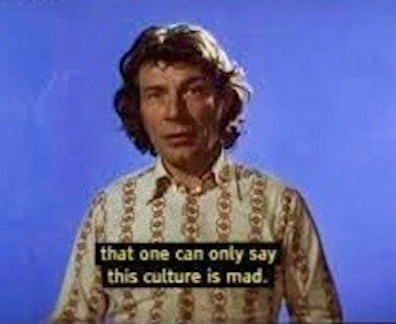

Well, yes, as the late art critic and novelist John Berger demonstrated in his classic 1972 BBC television series Ways of Seeing.

This wasn’t really Berger’s primary goal–more of a by-product of his reasoning. Ways of Seeing began by examining the long tradition of European oil painting and its actual, often-mystified purpose of displaying the power and possessions of the wealthy. Then, Berger turned his attention to advertising, which he suggested had taken up the role once played by fine art.

Artists from Rubens to Rembrandt and up to the moderns were, in considerable measure, devoted to painting things realistically, especially the property and womenfolk of the landed aristocracy. On the other hand, the ads Berger showed were fantasies. Yes, they portrayed expensive objects just as Hans Holbein’s painting The Ambassadors had. But ads are aspirational, giving the viewer images of life as it could be…if only one had enough money.

So, accepting Berger’s analysis, we can say that the advertising industry does indeed manufacture culture—portraits, landscapes, nudes (or nearly nudes), family tableau.

Berger suggested that these ads are effective—so much so that they have invaded our dreams. His examples included “the skin dream,” or succulent and inviting portraits of bodies on display. They also include dreams of remote and exotic locations that encourage us to buy a range of products.

Numerous corporate entities have also been successful in producing culture. Both Hollywood and European motion picture companies have been fabulously effective, as have music production companies from Sun Studios and Motown and right up to Darkroom/Interscope Records, the label behind the pop phenom of the moment Billie Eilish.

But such creation isn’t easy. We are all aware of countless, notorious flubs—from French rock ’n’ roll to the Hollywood movie Ishtar.

East Germany was responsible for some of the wildest, and most ham-handed, efforts at culture creation. Anna Funder’s Stasiland describes one attempt to replicate the success of American rock ’n’ roll dance. She quotes from an East German source:

“Today, all young people dance

The Lipsi step, only in lipsistep,

Today, all young people like to learn

The Lipsistep: it is modern!

Rhumba, boogie and Cha cha cha

These dances are all passé

Now out of nowhere and overnight

This new beat is here to stay!”

As Funder viewed dancers performing the Lipsistep, “in not one of this panoply of gestures do the dancers’ hips move. Their torsos remain straight—neither bending towards one another, nor swivelling from side to side. The makers of this dance had plundered every tradition they could find and painstakingly extracted only the sexless moves.…the Lipsi step was the East’s answer to Elvis and decadent foreign rock’n’roll. And here it was: a dance invented by a committee.”

Many establishment types were alarmed by the pelvis gyrations of Elvis Presley and Chubby Checker, but East Bloc leaders particularly envied the success of these Western cultural imperialists. Why couldn’t a committee invent an alternative to the Twist?

It seems that it don’t mean a thing if you ain’t got that swing.

Dinner: Turkey chili and a lettuce and oranges salad.

Entertainment: final episodes of Mhz’s German puzzler Man in Room 301.