Friday, November 20

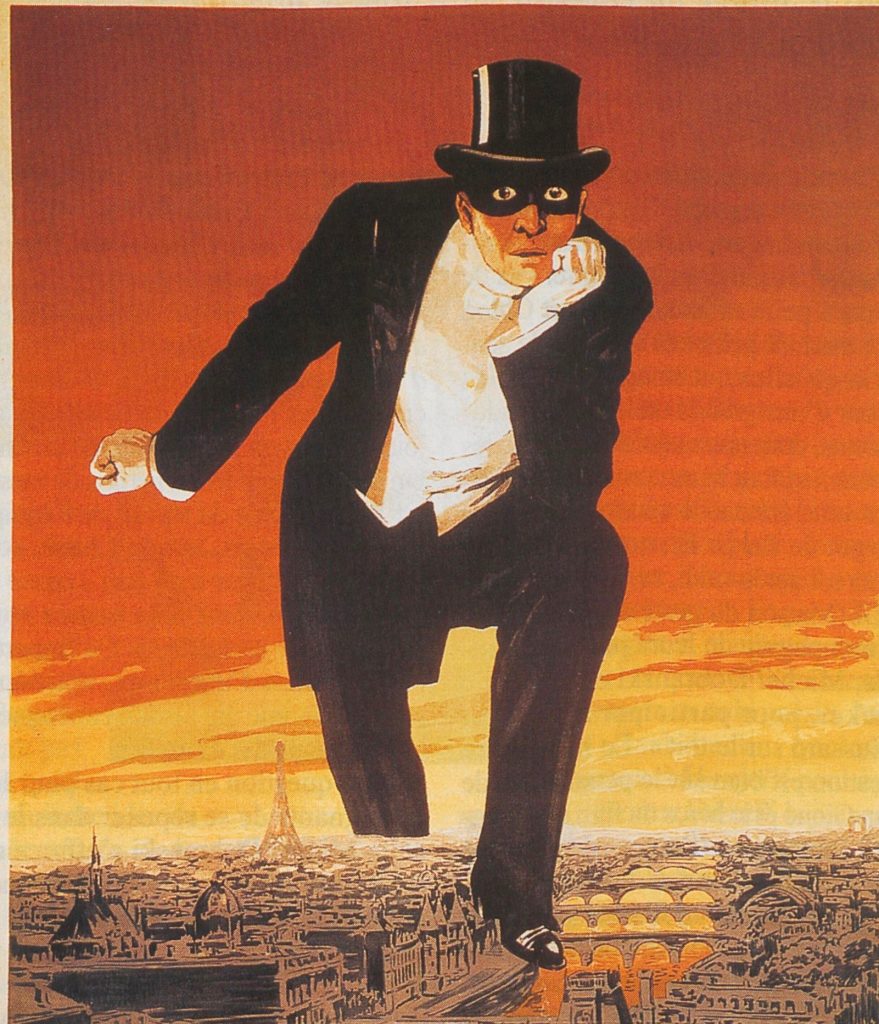

What is paranoia? In his classic and now much-referenced 1964 article “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” historian Richard Hofstadter defines paranoia as “a chronic mental disorder characterized by systematized delusions of persecution and of one’s own greatness.”

Hofstadter makes it clear that he is not a psychologist and is analyzing only a paranoid style. He finds this phenomenon to have existed in various historical periods among a variety of figures, including 18th century worriers over the activities of the Bavarian Illuminati, a precursor of the fraternity known as the Masons. Primarily, of course, Hofstadter is focused on the activities and writings of the mid-20th-century wacko political right wing in the United States. In the essay, he details some of the proclamations of infamous Wisconsin Senator Joe McCarthy and John Birch Society head Robert Welch.

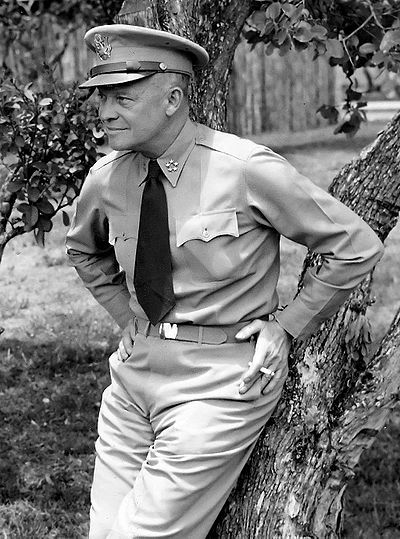

McCarthy, of course, won notoriety for discovering Reds Under the Beds of key U.S. institutions such as the State Department and the Army. He accused Secretaries of State George C. Marshall and Dean Acheson of participating in a Red “conspiracy on a scale so immense as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man.” Welch proclaimed that “Communist influences are now in almost complete control of our federal government.” Former Supreme Allied Commander and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was, to Welch, “a dedicated, conscious agent of the Communist conspiracy.”

Setting aside the particular subjects of McCarthy and Welch’s broadsides, the hyperbole, urgency, and delusions are all reminiscent of Trump and his cronies. In his proclamations, Trump wins elections and all other challenges by almost unfathomable margins. Allies and appointees he supports are uniformly, unbelievably marvelous.

But Hofstadter discovers one key difference with the Trumpist proclamations. The mid-20th-century right-wingers were assiduous quoters of sources and wielders of footnotes. Trump never offers any support for his over-the-top claims; it’s as if a Trump assertion alone should be sufficient. And for many Trump rank-and-filers, it seems to be enough.

The pre-Goldwater right wing were no more prone to accuracy than Trump. They simply saw the need to mimic academic and legalistic forms. Thus, Hofstadter notes “the very fantastic character of its conclusions leads to heroic strivings for ‘evidence’ to prove that the unbelievable is the only thing that can be believed.” (Hofstadter’s prose is itself so heroic that the temptation to quote him is overwhelming.) So it is that a 96-page pamphlet by McCarthy contains 313 footnote references, while Welch’s assault on Eisenhower has a hundred pages of bibliography and notes.

Trump and his surrogates, meanwhile, offer only “evidence-free” (in the Times’ phrasing) outbursts about questionable vote-processing in Nevada, purportedly suspicious mail ballots in Pennsylvania, and alleged votes by dead people in Michigan. South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham has pressured Georgia election officials to throw out absentee ballots since, he says, they were likely phonies. Trump lawyer Rudolph W. Giuliani has asserted that Detroit voting was “a fraud, an absolute fraud.”

Again, there is no evidence for any of these claims, and whenever they have come before courts, judges have not hesitated to disregard them. Yet, a poll released on Wednesday by Monmouth University found that 44 percent of Americans think the election smells—they say we do not have enough information about the vote count to know who won. Nearly one-third of the public believes Biden won only because of voter fraud.

How can Americans be so gullible? Or maybe the right word is….paranoid.

Dinner: a frittata with shallots, red bell pepper, and Dubliner cheese, along with braised potatoes and a green salad.

Entertainment: More episodes of Netflix’ The Crown.