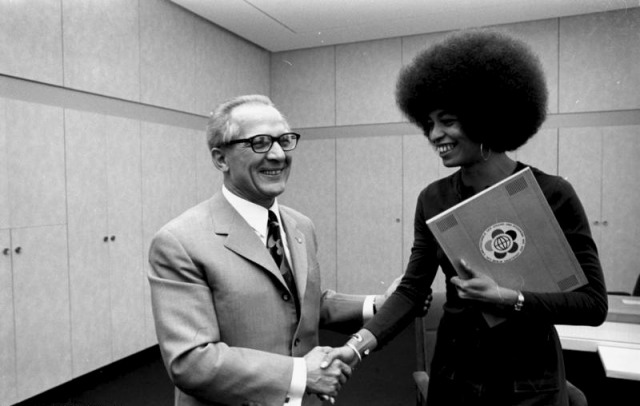

East German Communist biggy Erich Honecker with CPUSA leader Angela Davis. Photo by Peter Koard

Sunday, May 2

Readers could never be sure that the outlandish stories related by Polish writer Ryszard Kapuscinski were really nonfiction as he claimed. For instance, one anecdote in his book The Emperor concerned a member of Ethiopian autocrat Haile Selassie’s court—a figure known as the Minister of the Pillow. This person’s only known assignment: to quickly and discretely insert a pillow beneath the feet of the diminutive Selassie whenever the Emperor chose to sit on his grand throne.

The pillow helped to disguise Selassie’s short stature—and made him seem less like the preposterous Lily Tomlin TV character Edith Ann who sat in an oversize chair with her feet dangling above the floor.

Could there really have been a Minister of the Pillow?

Similarly, many stories about the East German secret police seem ripped from Kapuscinski’s pages. Could these honestly be true?

Before the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, East Germany was an East Bloc ally of the Soviet Union that kept an extremely close watch on its citizenry.

The East German Ministry for State Security, or Stasi, was the vast “internal army by which the government kept control,” in the words of Anna Funder, author of Stasiland. “Its job was to know everything about everyone, using any means it chose. It knew who your visitors were, it knew whom you telephoned, and it knew if your wife slept around. It was a bureaucracy metastasized through East German society: overt or covert, there was someone reporting to the Stasi on their fellows and friends in every school, every factory, every apartment block, every pub.”

In the last year of its existence, the Stasi employed 97,000 full-time operatives and had 173,000 unofficial informants in East Germany—a country of 17,000,000 residents. That works out to one operative for every 63 people. In Nazi Germany, there was only one Gestapo agent for every 2,000 citizens.

And during the forty-odd years that the GDR lasted, the Stasi arrested 250,000 people.

There are countless weird stories about the Stasi, some of which are related in Funder’s book.

For instance, she says that the Stasi developed a quasi-scientific, “smell sampling” method for keeping track of people. Everyone has his or her own peculiar odor, they believed, which we leave on everything we touch. Such smells can be captured and, with the help of “sniffer dogs,” used to find a match. To that end, the Stasi had a vast inventory of jars for smell samples, consisting of things like soiled clothing stolen from people’s apartments. “The Stasi would take its dogs and jars to a location where they suspected an illegal meeting had occurred, and see if the dogs could pick up the scents of the people whose essences were captured in the jars.”

Icky, no?

Another story. The Stasi had elaborate plans for a final day of confrontation with internal enemies of the regime—a Day X. On that date, yet to be determined, Stasi officers would arrest and jail precisely 85,939 East Germans, all listed by name on the plans. They imagined how all available prisons and camps, including former Nazi detention centers, schools, hospitals and factory holiday hostels, would house these prisoners

Tis the final conflict, as “The Internationale” would have it.

To write her book, Funder found many people who had contact with the Stasi. In one case, a young woman was summoned to a Stasi major’s office, Room 118 at a police station. There, the officer produced a pile of her private love letters, communications with a former Italian boyfriend whom she had met during a trip to Hungary, and he grilled her about them. The Stasi officer, who was exaggeratedly polite, focused on individual words in their “private lovers language,” including their pet names for each other. He knew a great deal about this boyfriend—his job, his house in Umbria, the make of his car. The Stasi were “very interested” in this friend—but the woman said she couldn’t help them since the two had split up. The major let her leave, but gave her his business card and said she should not hesitate to call.

Which she did later, after discussing with her mother this invitation to become an informer. When the Stasi officer came to her home along with another official, the woman told him she was going to invoke her right to communicate directly with the country’s Communist leader, Erich Honecker, and make a complaint. Weirdly, this seemed to set the officials back on their heels—there was no need to get Berlin involved, they said. She never knew why the Stasi feared this communication with Honecker…but somehow, she had won.

Not everyone won, of course. Between 1961 and 1988, over 100,000 GDR citizens tried to escape to the West and over 600 of them died in the process. The Berlin Wall—known internally as Die Antifaschistischer Schutzwall, or the Antifacist Protection Rampart—was, the East German regime declared, “a service to humanity” in that it walled out imperialism. And of course it walled out most everything else.

Dinner: chicken salad and tomato-red pepper soup.

Entertainment: episodes of the old sitcoms Cheers and Seinfeld.