Wednesday, May 20

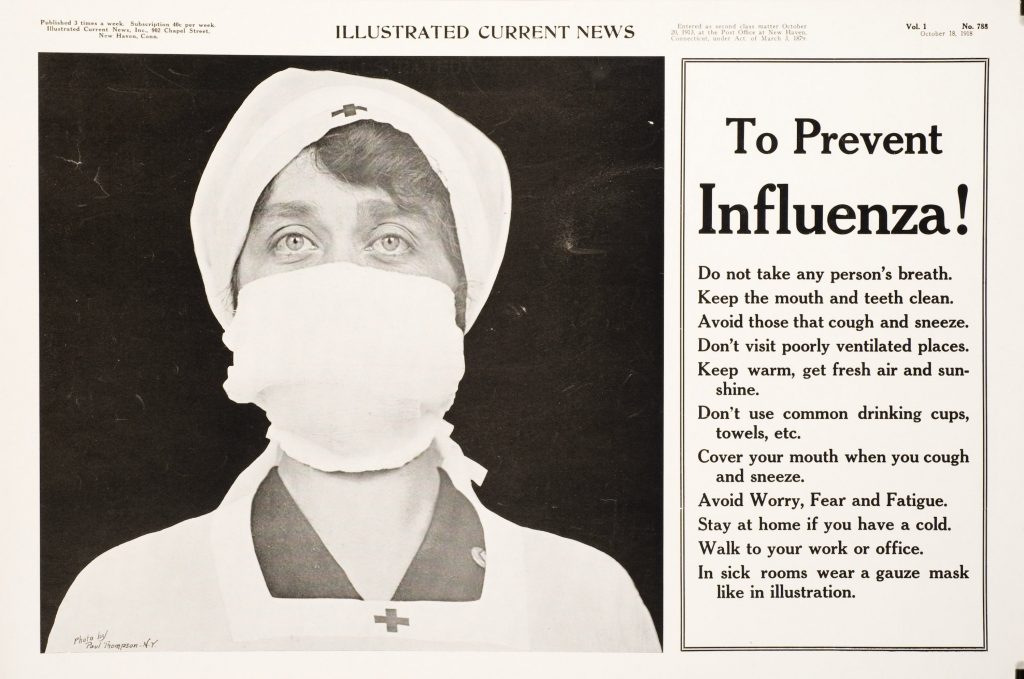

It turns out that but for the 1918 influenza pandemic, one of today’s most fashionable exercise routines might never have existed. It’s a curious and perhaps frivilous sidebar to a tragic, world historical event.

At the time of the war, German alien Joseph Pilates was interned by Britain along with 23,000 other suspicious types in Knockaloe Camp on the Isle of Man. The internees were there as both an anti-German wartime precaution and as part of the pandemic lock-down.

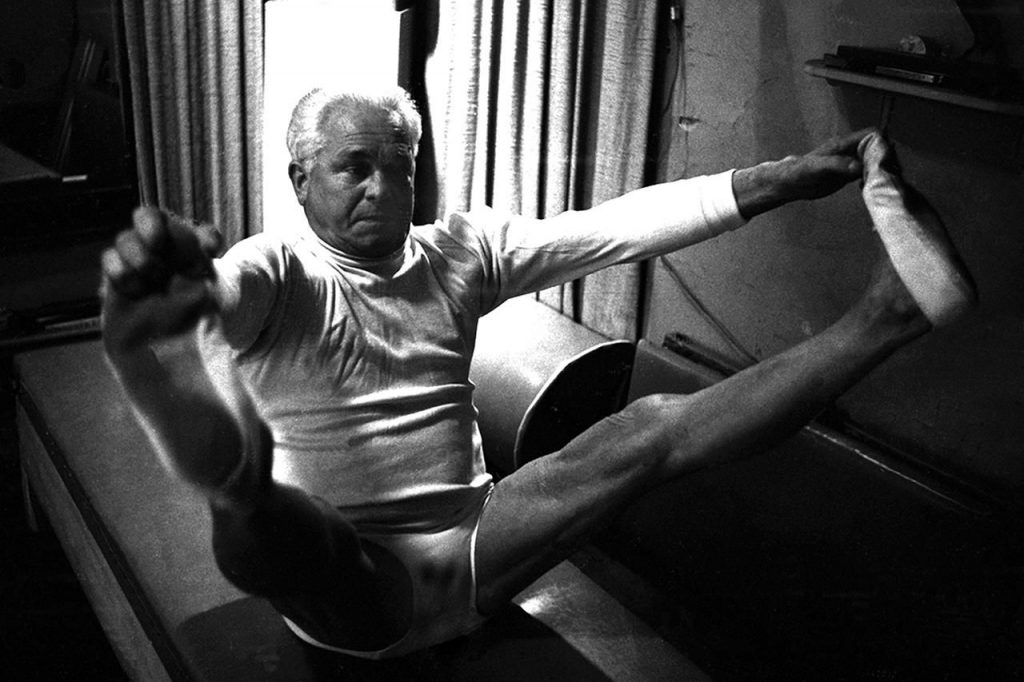

In an effort to relieve boredom, the former boxing coach invented a new exercise regimen that used a variety of improvised machines made of bits of wood, old beds, and salvaged springs to provide resistance. His exercises also drew upon his observations of the ways of the island’s feral cats.

Some years later, after he’d relocated to New York City, he opened a gym and began making furniture and exercise machines including one that resembled a spring-equipped cot that he called “the reformer.”

His “contrology” system, with its emphasis on strengthening the body’s core, drew many dancers, some of them suffering from injuries. Central to his ideology was the assertion that, among those who’d adopted his regimen during the 1918 island quarantine, “nobody got sick.” The system’s 34 mat exercises remain central to the instruction, which is now known by the inventor’s surname, Pilates.

During the current lockdown, many people have been looking online for exercise instruction. I haven’t found much that’s to my liking: The yoga aimed at seniors seems a tad too mild, while other instruction often involves some jumping around or vertigo-inducing getting up and down from a prone position. But there are a lot of videos online, so I intend to keep looking.

We’re anticipating another Peapod grocery delivery tomorrow afternoon, with a mixture of eagerness and trepidation. Some of what we’ve requested is sure to be “out of stock,” and there will be some surprise substitutions. We’re still laughing about the number of packs of frozen green beans that we’ve received, most as substitutions for our orders of green peas. There is also the anxiety about—and weariness with—just how much we should be disinfecting cans and boxes, wiping down fresh vegetables, and quarantining everything.

Emily has been regularly taking her Duolingo lessons in Spanish and finishing off one after another New York Times crossword puzzle, mini puzzle, Spelling Bee, Letter Boxed, and Tiles puzzles.

And now, it’s time for my walk, which proves uneventful.

Tonight’s dinner: more chicken paprikash and lettuce salad.

Entertainment: More episodes of Occupied.