Tuesday, May 19

A company called Moderna has developed a COVID-19 vaccine that has shown promising results in early tests on humans. The announcement raised public hopes and sent the company’s stock soaring. But past events should prompt skepticism.

The 1918 “Spanish flu” pandemic—the worst in U.S. history—saw the early development of a vaccine, too. Some 18,000 people were inoculated in San Francisco. But unlike the vaccines that had already been developed to treat anthrax, diphtheria, meningitis, rabies, and smallpox, this vaccine proved ineffective. The “Spanish flu” was a virus—and scientists knew little about viruses, which couldn’t even be seen until the development of the electron microscope in the 1930s.

I’ve been meaning to learn more about the 1918 influenza epidemic, and this afternoon I finally watched the American Experience film “Influenza 1918” The film is fascinating.

There’s also a PBS timeline of 1918 events. It differs a bit from the CDC’s timeline.

The 1918 flu wasn’t “Spanish” at all. It probably first appeared in the spring of 1918 at a Kansas army base, Fort Riley. It spread quickly: By noon of the first day there were over 100 cases at the base and 500 in the first week. After 48 deaths, the sickness began to wane. But American soldiers traveled to the Western front of World War I—and took the infection with them.

Soon this strain of influenza infected other American soldiers as well as English, French, and Germans.

By September, soldiers returning from the front to the U.S. brought the flu back with them. A major outbreak took place at Camp Devens near Boston. Doctors were shocked at seeing how this strain, much more potent than any flu they had seen before, turned patients’ skin blue, resulted in a bloody sputum, then led to pneumonia, and, often within only a few hours, death. The disease was carried from one military base to another. Soon, it was out among the civilian population—in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and across the U.S. Before long, it was in small towns in the Midwest and West.

The war’s exigencies had made the outbreak worse. Focused on defeating the Kaiser, Americans had pulled together in large groups. They labored in factories, attended mass rallies and war bond drives, and marched in thousands-strong parades. Then soldiers were massed together and put on troop transports.

Like today, there was no shortage of officials looking to pin the blame on foreigners. Lt. Col. Philip Doane, head of the Health and Sanitation Section of the Emergency Fleet Corporation, suggested that Germans somehow planted the infection.

Quackery flourished: Some people wore little flasks with turpentine or camphor around their necks. Others turned to prayer, following the advice of evangelist Billy Sunday who said sin was to blame and prayer would end the epidemic.

Hospitals overflowed, but many doctors had been sent to Europe. The infected had raging fevers, nosebleeds, and lungs filled with fluid, from which many literally drowned.

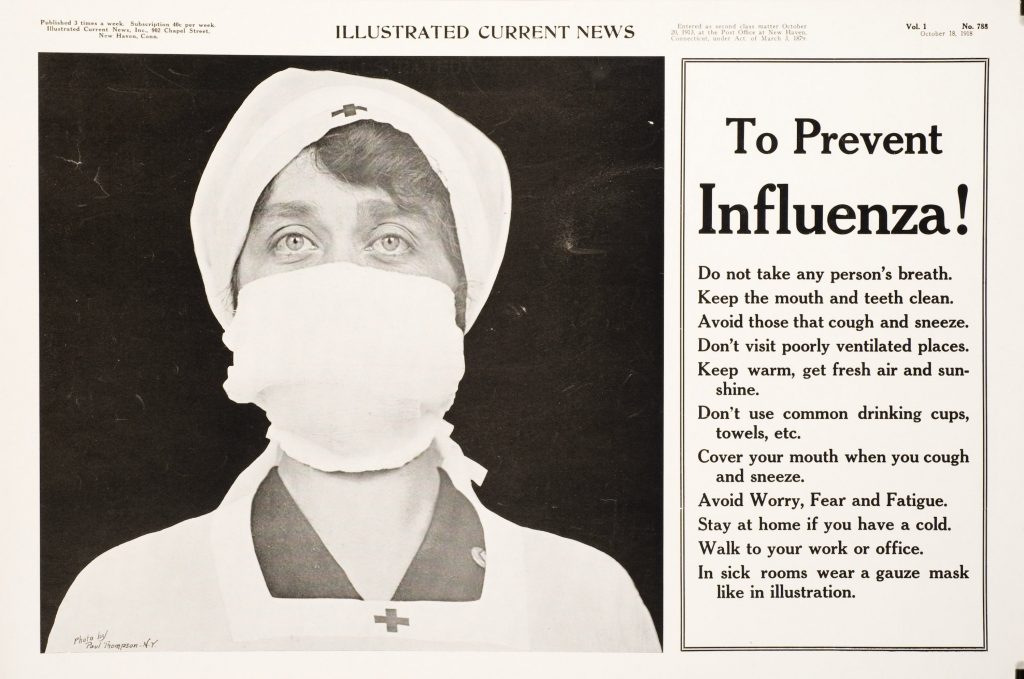

Laws required that people wear masks. Public gatherings were ultimately banned. Schools, farms, and factories were shuttered, but the death rate kept rising. Oddly enough, the young and strong seemed most vulnerable, particularly those between 21 and 29 years of age.

October proved to be the worst month—869 New Yorkers died in one day and 195,000 Americans in a month. There were suicides and a wave of violence, often within families.

Then, by early November the death toll on the east coast fell. The incidence of new cases dropped abruptly. Herd immunity may have developed or the virus may have mutated to a less lethal strain.

On November 11, the armistice was declared in Europe. Thousands in the U.S. attended victory parades, most wearing masks.

But some 500,000 to 850,000 Americans died in the pandemic. Around the world, 30 to 50 million died.

Why have these frightening events been largely forgotten? History books have focused on the battles and drama of the Great War, although more soldiers and civilians fell victim to the pandemic than to war. The invisible scourge went away, and afterwards Americans could imagine that science and civilization had prevailed. Until now, that is, when science seems something less than all-powerful.

Tonight’s dinner: chicken paprikash, pasta, and green salad.

Entertainment: One episode of Occupied plus one installment of Our Planet.